Labor Day means different things to different people.

The Labor Day Telethon

For me, it’s hard (try as I might) to escape the association between Labor Day and the Jerry Lewis Muscular Dystrophy Association Telethon. Though it’s been several years since we’ve organized a direct action protest, the Internet continues to provide us with opportunities to educate and inoculate people against the Telethon’s pity paradigm.

The Internet also provides us with more evidence of the hypocrisy of a man who claims to be a “humanitarian” (and of a shallow showbiz industry that validated that title with a 2008 “Humanitarian Oscar Award.”) During a recent interview on Inside Edition, Jerry Lewis avowed that he would punish Lindsay Lohan physically for her recent transgressions. “I’d smack her in the mouth if I saw her. I would smack her in the mouth and be arrested for abusing a woman! I would say, ‘You deserve this and nothing else’ — whack! And then if she’s not satisfied, I’d put her over my knee and spank her.” If you want to torture yourself by watching it for yourself, here’s the video clip.

(Some people, perhaps tired of the media coverage of Lohan’s nonsense, seem to find Lewis’ statements funny. But my philosopher crip friend Joe Stramondo puts them in perspective: “Jerry Lewis again uses a narrative that masquerades violence/oppression as ‘help’ by obscuring it with pity. This time it’s women who he pities. So, I guess sexism and ableism have something in common for him.”

I would recommend avoiding Jerry Lewis and the Telethon altogether this weekend. For an edifying alternative, check out my friend Mike Ervin’s sassy response to the Telethon. He made a video called The Kids Are All Right (long before the current lesbian family dramedy), about the activist group Jerry’s Orphans.

By the way, check out the Denver Post on Tuesday for a spot-on column describing disability activists’ objections to the Telethon.

Labor Force Diversity (Including Disability)

This Labor Day, too many people are still jobless, and the situation is worse for people with disabilities. In August 2010, only 22 percent of people with disabilities were participating in the labor force, while 70.2 percent of non-disabled people were in the labor force. The unemployment rate for those with disabilities was 15.6 percent, compared with 9.3 percent for persons with no disability.

There are many complex reasons for this disparity. Certainly one reason are the negative attitudes that some employers and coworkers have toward people with disabilities. Even those who are not actively hostile to disabled folks may not have considered or understood the need to actively recruit, hire, and accommodate workers with disabilities.

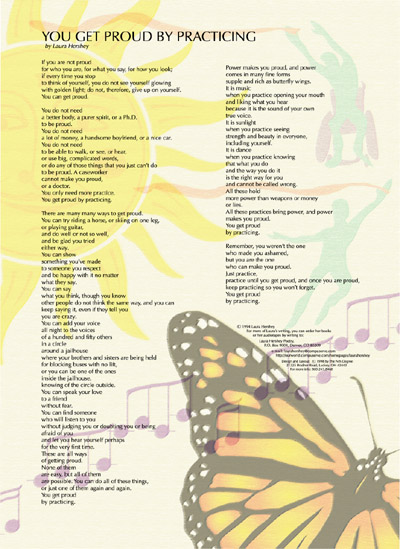

To try to address the lack of awareness, the U.S. Department of Labor (which provided the above statistics) sponsors National Disability Employment Awareness Month (NDEAM). This year, I have a direct role in this effort. A few lines of my poetry, along with a piece of my digital art, appear on the official poster for NDEAM. The poster is available for FREE to employers, advocacy organizations, schools, or anyone else who requests it. Even cooler, it’s available in eight languages, including Navajo and Lakota. Go to the DOL website at http://www.dol.gov/odep/pubs/ndeam2010poster.htm to order or download your poster(s). Did I mention they’re FREE?

Can a public awareness campaign like this make a real difference in improving disabled people’s employment prospects? Who knows? But I think the poster turned out beautifully, and I like the emphasis on disability as a part of diversity. I also know that the DOL under President Obama is being managed by some hard-working, progressive people, including Secretary Hilda Solis; and Kathy Martinez, Assistant Secretary for the Office of Disability Employment Policy.

(And I should probably add that my comments above about MDA and Jerry Lewis have no official government endorsement!)

Labor in Service of Independent Living

Labor Day celebrates workers, and my favorite workers are those who support people with disabilities in living in the community. Call them attendants, personal care assistants (PCAs), personal assistants (PAs), home health aides, helpers, even certified nurses’ aides (CNAs) – whatever you call them, they are crucial to the disability rights movement.

Good attendants do more than just enable a disabled person to live outside an institution. They allow us to live a life of maximum independence, functioning at our own personal best and working toward our life goals.

In just the past few months, here are just some of the ways that home care workers have made a huge difference for my health and/or independence and/or work:

Â

All of my current attendants are great – highly competent, reliable, smart, cooperative, and calm amidst craziness. And I have enough experience under my belt to know how hard life can be when that’s not the case. (Attendant horror stories belong in another blog post.)

Another whole column – or a whole book – could be devoted to discussing the labor rights, or lack thereof, of home care workers. Given what they do, they are for the most part underpaid, uninsured, and unsupported by society as a whole. They usually don’t get paid sick days or vacation days. In only a few states do they have union representation.

So many entities make inflated profits by exploiting our disability-related needs. But the people doing the real, hard work that helps us live independently don’t get nearly enough. People with disabilities and our support workers need to organize together, to demand fairer policies and more resources for this work.

For now, though, I’ll use Labor Day as a day to express my appreciation for these indispensable workers.

The End of Summer

Labor Day also represents the end of summer, if not officially, then at least traditionally. My most recent “Life Support” blog post for the Reeve Foundation website describes one of the highlights of my summer. Surf on over there and read “Roughing It, Accessibly, in a Colorado Yurt.” And while you’re there, check out the other great bloggers, articles, and information.